KINIGUIDE | The Memali Incident has once again resurfaced in Malaysia’s political discourse, nearly 32 years after the tragedy took place.

The issue was brought up during a forum where former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad spoke on Aug 13, but his response was interrupted when violence broke up at the forum.

The fracas at the forum reignited interest in the Memali Incident. Even prior to that, however, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi had also mentioned the incident while attacking Mahathir in a speech in Baling.

In this instalment of KiniGuide, we will dust off the history books and explore what happened on that fateful day on Nov 19, 1985, when police attempted to arrest PAS leader Ibrahim Mahmood (Ibrahim Libya) and his followers.

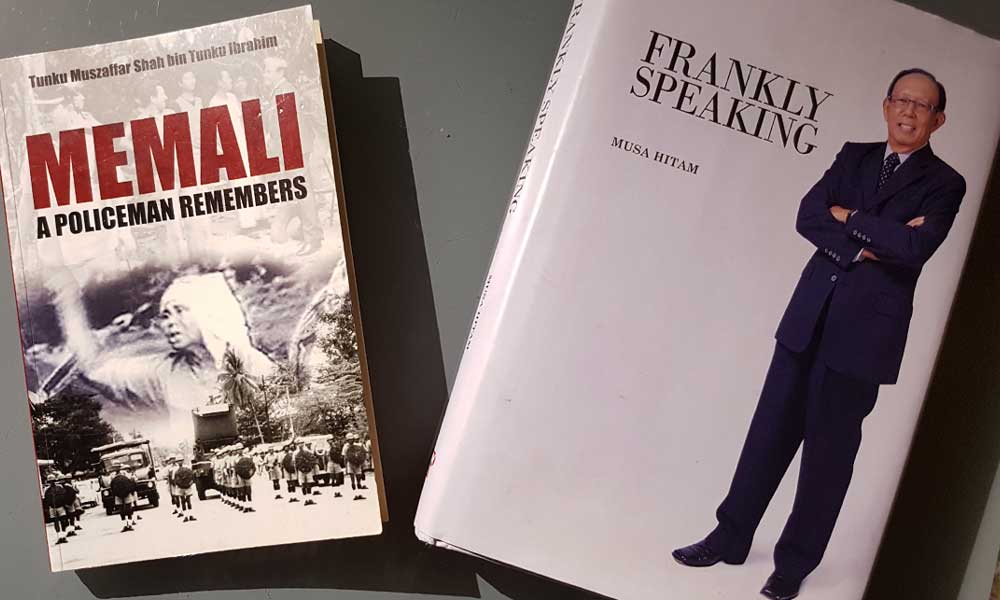

This KiniGuide is based heavily on the book ‘Memali: A Policeman Remembers’ by the then Baling OCPD Tunku Muszaffar Shah Tunku Ibrahim. It was published in 2011.

The book contains the district police chief’s first-hand account, as well as that of one of Ibrahim’s followers Yusuf Husin, who later became a senator. It also contains an English translation of the government white paper on the Memali Incident, which was tabled in Parliament in 1986.

Musa Hitam’s 2016 autobiography ‘Frankly Speaking’ was also delved into. He was the deputy prime minister and home minister at the time of the incident, and his book included a chapter on it.

The political climate

There was hostility between Umno and PAS. The two parties had become partners in the Alliance coalition in 1972, but they had a falling out and PAS withdrew from BN in 1977. The Alliance coalition had been rebranded as BN in 1973.

Following the 1979 Iranian revolution, religious conservatives within PAS became increasingly influential, and the rivalry with Umno took on a more religious tone as PAS leaders began branding Umno members as infidels.

The government white paper includes the current PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang’s famous “Amanat Haji Abdul Hadi Awang” (Abdul Hadi Awang’s Message) as an example of this increasing radicalization. The message was an excerpt of a speech he made in 1981 and was widely disseminated amongst PAS members.

In the excerpted speech, Hadi claimed that PAS opposed BN and Umno because it perpetuates a “colonial constitution” and “infidel laws”, and thus opposing them is a sacred duty.

“Therefore, we oppose them. Believe me, brothers, our struggle is jihad, our speeches are jihad, our donations are jihad. And because we are fighting these groups, if we die in the fight, we die, martyrs, we die Muslims,” he was quoted as saying.

Who was Ibrahim Mahmood?

According to the government white paper, Ibrahim was born in Kampung Charok Puteh on July 1, 1942, which is near Kampung Memali.

He was schooled up to Standard Six before moving on to pursue religious studies, eventually obtaining several degrees, including a diploma in Islamic missionary from Ma’ahad Dakwah, Libya. This had also earned him the moniker Ibrahim Libya.

He returned to Malaysia in 1974, where he was attached to the Prime Minister’s Department’s Religious Department until he resigned on 1976.

He then went back to his hometown to teach at a religious school, and eventually set up his own school, Madrasah Islahiah Diniah in Memali.

“We loved him for his sincere interest in our welfare. When he returned from Libya, he worked in the Prime Minister’s Department in Kuala Lumpur. He could have done well for himself, but he chose to return to Memali.

“He was a charismatic speaker, and he used his gifts to inspire a religious revival in Memali. Before he returned to us, the people of Memali were notorious for their lack of interest in religion. Ibrahim Libya and a group of his followers - myself included - revived the religious school in Memali,” Yusuf recounted in the Memali book.

Why the government went after Ibrahim?

The government white paper portrayed Ibrahim as a firebrand speaker inculcating “extremist attitudes” amongst PAS members and supporters.

Among others, he is supposed to have said in a ceramah on June 12, 1984, in Kuala Nerang, Kedah, “Fight anybody with the sword, be it your brother, uncle, or grandparents, and do not associate with them, for they are no longer Muslims.

“Do not associate with Umno members who have become infidels, the meat of animals they slaughter, and whatever they cook, are haram. Let us not attend their feasts.”

The paper pointed to Ibrahim’s sermons as the cause of increasing hostility towards government personnel around Memali, and increasing polarisation amongst the Memali villagers and even within PAS itself.

The report also accused Ibrahim of plotting to instigate a conflict by freeing several PAS members from detention and then bringing them together for a ceramah to lure the police into taking action. He and his supporters supposedly solicited other PAS followers to back the plan.

“They believed that in so doing, they could spark off a clash between the police and PAS members,” the report said.

In addition, the report said Ibrahim had plotted to topple the government by force during two meetings in early April 1985, for which the group Gerakan Revolusi Islam was set up with Ibrahim as its president.

“It soon became clear that Ibrahim was the leader of an Islamic cult. Ibrahim’s brand of Islam was alarming, and it was obvious his influence had to be curtailed. A series of police operations were, therefore, launched to try to arrest him peacefully under the Internal Security Act (ISA),” Musa recounted in his biography.

An abortive arrest

The first attempt to arrest Ibrahim took place at about 2.45am on Sept 2, 1984, at his house in Memali.

According to Tunku Muszaffar's account, a meeting about the raid had taken place at the Sungai Petani district police headquarters: A Special Branch (SB) team was to arrest a target in Sungai Petani, while another Special Branch team to arrest Ibrahim, in Memali.

Both arrests were supposed to take place simultaneously on the early morning of Sept 2, 1984, when both targets take their children to school. Tunku Muszaffar was to provide support for the Baling SB team.

However, there were two complications to the plan.

Both Tunku Muszaffar and Musa recounted that Musa had given an order that absolutely no force is to be used against the two targets. If resistance is encountered, the police are to withdraw immediately to avoid bloodshed.

“I can’t believe my ears. Ibrahim Mahmood has a licensed gun and could well use it against the arresting party. If he does, my men are, apparently, barred from defending themselves,” Tunku Muszaffar said.

He was highly critical of his superiors in Bukit Aman for choosing to follow the home minister’s directive, saying that such “tall and ridiculous” orders that are not in line with police procedures should have been firmly rejected.

The other complication was that instead of conducting the arrest on the day after the meeting, the Sungai Petani team had arrested their target on the very same day. This prompted the police to attempt to arrest Ibrahim at his home sooner than planned, fearing that he may hear of the Sungai Petani arrest and attempt to escape.

When police arrived, however, Ibrahim would not respond when the police called out to him, though footsteps were heard inside the house.

Tunku Muszaffar said an alarm was later sounded, and between 20 to 30 people approached with sharpened bamboo and other weapons. The police withdrew in compliance with Musa’s instructions.

Escalation

According to Yusuf, Ibrahim had gone into hiding following the botched arrest, but he and his followers were determined to bring him back and offered to guard him.

“The situation was ridiculous. We had a highly qualified religious teacher in our midst, but we were unable to benefit from his teaching. So we brought him back to Memali and guarded him ourselves,” he said.

Tunku Muszaffar said that by the time the final attempt to arrest Ibrahim was made, the villagers had dug trenches and built obstacles around Ibrahim’s house. Guards were also posted, and weapons including firearms were gathered.

According to the government white paper, the villagers had ‘misread’ the police withdrawal as a sign of weakness and had become emboldened.

“They, therefore, became more arrogant, rude, and bold in challenging the authorities. Henceforth, policemen on duty to keep peace and order around Kampung Memali were frequently jeered at, abused, and challenged by Ibrahim Mahmood’s followers,” the report said.

It said the arsenal gathered at Ibrahim’s house included swords, parang, catapults (lastik), sharpened bamboos, torches, arrow guns and arrows, Molotov cocktails, and fish bombs. In addition, shotguns were obtained from members of the Malaysian People’s Voluntary Organisation (Rela).

The Memali book also contains an account of an incident on the night of Oct 20, 1985, where a group of more than 10 policemen, including Tunku Muszaffar, were surrounded and were nearly lynched by an armed mob at a PAS rally at Ibrahim’s madrasah.

Tunku Muszaffar said the crowd - armed with sharpened bamboo, machetes, daggers, and sticks - were incensed that police had earlier confiscated two daggers from a van at a roadblock leading to the venue.

This was until Yusuf - then a Baling PAS committee member - intervened to calm the crowd and convinced them to take the police hostage instead. They were released after Tunku Muszaffar returned the two daggers, which Tunku Muszaffar stressed was done under duress.

Ops Angkara

The final police operation against Ibrahim was codenamed Ops Angkara, slated to commence Nov 19, 1985, at 8.30am.

Muszaffar said the plan calls for two troops of the Federal Reserve Unit (FRU) to cordon off the area around Ibrahim’s house and provide cover for the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) team making the arrest.

The FRU would depart from an Area Security Unit camp in Tanjung Pari, which is to the north of Memali. It would do without its standard complement of a rifle section and would be equipped with tear gas, batons, and rattan shields instead.

However, Tunku Muszaffar and two of his men accompanied the FRU team. The subordinates had M16 assault rifles. Also with the FRU, were SB officers tasked with taking videos of the day’s events, and a CID officer with arrest warrants to pick up Ibrahim and his followers.

Meanwhile, two units of the Public Order and Riot Unit (Poru) were to converge from the opposite direction (Baling, to the south of Memali) and would be equipped with armoured vehicles and would stop about 200 metres from Ibrahim’s house. They would be accompanied by the Police Field Force, which would be armed and included the VAT69 police commandoes.

By then, Tunku Muszaffar said Ibrahim’s firearm licence had been cancelled, and the shotgun had been surrendered to the police by one of Ibrahim’s relatives.

However, an order to cancel all firearm licenses in the area had yet to be implemented. This included shotguns issued to Rela members in the area.

According to the government white paper, a total of 576 police personnel were involved in the operation. However, the group converging from Baling Town had been obstructed by “women and children armed with sharpened bamboos and wooden sticks”.

It also said there were about 250 people at Ibrahim’s house, most of whom rushed there by the sounds of a drum at Ibrahim’s madrasah and the bell at Ibrahim’s house.

Shots fired

When the FRU arrived at Ibrahim’s house, Tunku Muszaffar said the Poru were nowhere to be seen, so the FRU proceeded alone.

He was at the time perched at the turret on top of the FRU command vehicle together with the FRU commander, the commander’s assistant, and a police photographer.

It was drizzling. The FRU personnel disembarked from their vehicles about 100 to 150 metres away from Ibrahim’s house to form up in front of the command vehicle.

Tunku Muszaffar said it was at this time when the police were pelted with pebbles from the bushes on both sides of the road. The FRU pushed on to about 50 metres from the house, where Tunku Muszaffar said Ibrahim’s people emerged from the right side of the road armed with swords.

The FRU commander ordered the group to disperse. When they ignored, the FRU troopers fired tear gas shells at them. This caused the group to disperse, except for one lone swordsman.

Tunku Muszaffar said as the swordsman began to charge, the FRU troopers made a run for their vehicles. He then heard shots being fired from the bushes and saw some of the FRU troops fall to the ground.

A shot from one of his men’s M16 killed the swordsman as he was trying to board the command vehicle, but gunfire from the bushes continued.

“A shot missed me and hit the police photographer on his right cheek. He was standing on the turret next to me to my left. After a while, the ferocity of the attack subsided. I then took the police photographer to the lower deck of the command vehicle.

“On the lower deck, I saw an FRU sergeant being carried up into the command vehicle. He was badly wounded, blood oozing from his mouth. I also saw that one of my men, the police constable, had gunshot wounds on his left kneecap.

“I later came to know that he died as a result of the gunshot wounds sustained,” he recounted.

All four police personnel who perished in the Memali incident had died or mortally wounded during this first skirmish of the day.

Inside Ibrahim’s compound

Yusuf said the events of Nov 19, 1985, came as a shock, and gave the following account in the Memali book:

“We never dreamt the police would turn their guns on us. Ibrahim Libya himself did not want us to attack the police. He said we should stay within the compound and leave our fate to Allah. I gave orders to that effect and made sure the gate was securely fastened to prevent anyone from entering or leaving.

“When tear gas was first fired, one of the children inside the compound fainted. A secondary school teacher saw this and thought the child had died. He ran out of the compound with a machete and was shot.

“Someone in our group returned fire. As a member of the government’s paramilitary civil volunteer corps (Rela), he had a shotgun. I don’t know if any of the police were wounded.”

The cavalry arrives

The FRU waited until about 11am amid sporadic stones being pelted from the bushes, but the shooting seemed to have stopped, Tunku Muszaffar wrote.

It was then a V-100 armoured vehicle from Poru showed up and arrived at the gate of Ibrahim’s house. Molotov cocktails were thrown at it, and Poru retaliated by throwing tear gas canisters into Ibrahim’s compound.

He said the FRU command vehicle then approached to about 20 to 30 metres of the house but then retreated to seek shelter from Poru’s gas attack.

When the gas dissipated, Tunku Muszaffar said he joined the operational commander who was already walking towards the gate and appealing to those inside Ibrahim’s house and compound to surrender.

Tunku Muszaffar said he was then told by the commander to read out a warning that had been prepared by the Kedah CID, which he did. He also appealed for Ibrahim to send out the women and children but to no avail.

Storming the gate

After repeated futile attempts to coax the villagers to surrender, the commander then gave them five minutes to reconsider and the officers started to leave the gate.

“As I walked away from the gate, barely a few paces, toward the police vehicle, I suddenly heard incessant gunfire, including the sound of automatic fire. I dropped to the ground and took the ‘stand to’ position.

“I saw a lot of people running out from the compound of the target’s house. Some were injured, many were arrested by police teams. I then went back to the front of the gate.

“At that time, when people were being injured and killed, there was a sudden heavy downfall. It rained cats and dogs. I then saw Ibrahim Mahmood being taken out of the compound of his house on a stretcher. Although he was still alive, he was badly injured and breathing heavily,” Tunku Muszaffar wrote.

He said he was unsure what led to the renewed outbreak of violence well before the five-minute grace period ended. He postulated that there may have been some miscommunication, or perhaps that some members of the police had been attacked by the mob.

The official version of events states that an armoured car was used to break through the gates at 12.15pm. The operational commander and a group of police personnel were trying to separate the women and children from the men, while urging the men to surrender. Few complied.

“The police personnel were fired at with shotguns by supporters of Ibrahim bin Mahmood. At that time too, the police were attacked by Ibrahim bin Mahmood and his followers armed with parang and swords.

“As a result, seven police personnel were seriously wounded. To defend themselves and to thwart the attacks, the police ultimately had to use firearms.

“Eight of the attackers, including Ibrahim bin Mahmood was killed in the yard of the house. Four other supporters of Ibrahim bin Mahmood were killed by the gate of his house. Another was killed in the back of Ibrahim bin Mahmood’s house when he and several of his followers attempted to attack the police personnel surrounding his house,” the report said.

The report also said that a large number of those inside Ibrahim’s compound had wanted to leave, but was prevented from doing so due to death threats by Ibrahim’s supporters.

Yusuf meanwhile said that when Ibrahim’s one-year old daughter fainted due to exposure to tear gas, a relative had carried her out through the back of the house and was let through by the police.

As for the clash itself, he surmised it in just one paragraph: “When the police finally entered the compound and attacked us, there was chaos. Our weapons were simple traditional ones – machetes, spears, and sharpened bamboo.

“After it was over, I was rounded up and taken to Alor Setar where I was placed in solitary confinement,” he said.

After the dust settled by 1.30pm, the final death toll stood at 18 people – four from the police, and 14 civilians including Ibrahim who succumbed to his wounds. In addition, 37 people were injured, of whom 23 were police personnel, and 14 were civilians.

The government white paper did not provide figures on the number of people arrested. Musa said in his autobiography that there were about 160.

Aftermath

According to Musa in his book, the acting inspector-general of police (IGP) Amin Osman came into his office one early morning on Nov 19, 1985, and that was when he first learnt of the Memali Incident.

Before Amin could finish his briefing, Musa said he called the then prime minister, Mahathir, and then they both went over to Mahathir’s office where the briefing continued in Mahathir’s presence.

“To the best that I can remember, I only knew about the tragedy through the acting IGP’s briefing, even that was after it happened. I can only surmise that events unfolded so swiftly that the police had to act in line with their general orders,” he said.

At the time, Musa had borne the brunt of the blame for supposedly orchestrating the bloodbath in Memali, as media reports claimed that Mahathir was on an official visit in China at the time, thus leaving Musa in charge as acting prime minister as well as the home minister.

“Some quarters later alleged that I was the one who decided on the timing of the operation. It was also alleged that I decided how many police should be deployed and that I also directed the operation.

“In my defence, I would like to say emphatically that as a minister, you do not make operational or tactical decisions. Rather, you formulate policy.

“In this case, I set the rules by saying that we needed to monitor the situation and be mindful of any threats to public security, but force was not to be used. As far as the police were concerned, it was their duty to send me regular reports in my capacity as minister of home affairs and make sure that law and order were maintained and security was not compromised,” he wrote.

He also clarified that Mahathir’s trip to China was in fact scheduled for Nov 20. He said he had advised Mahathir to postpone the trip, but Mahathir decided to go ahead with it instead.

He said it was only after Mahathir had departed when he became acting prime minister. This was also the time when he had finished gathering facts about the Memali incident and started making a statement on the issue in Parliament and in press conferences.

As for Tunku Muszaffar, he said the acting IGP arrived in the evening from Kuala Lumpur to be briefed on the situation.

However, Amin was not a part of the briefing, as the acting IGP, he was told to leave immediately to declare a curfew in the surrounding areas under Section 52(1) the ISA. No one was to be allowed outdoors from 3pm to 5am until the curfew was relaxed.

Yusuf meanwhile, was taken to Kamunting detention centre, where he was held under ISA with 35 other Ibrahim followers.

In retrospect

Among Tunku Muszaffar’s criticisms of the Ops Angkara was the decision to take on Ibrahim in his stronghold, which he said was “not wise”. He suggested that arresting him anywhere in the Baling district would not have been appropriate due to the presence of his supporters.

Instead, the SB should have arrested Ibrahim while he was on his way to give political talks in other location in Kedah, in Perak, or in Penang.

He also criticised the lack of coordination amongst the police, including the Sungai Petani SB’s move to arrest their mark ahead of schedule instead of working in concert with the Baling SB team tasked with arresting Ibrahim in 1984.

“His actions had, in a way, precipitated the botched attempt to arrest Ibrahim Mahmood and eventually, the bloodshed between the police and Ibrahim Mahmood’s supporters,” he said.

Yusuf meanwhile said the authorities should not have used the ISA (a now-abolished law that allows for detentions without trial) against Ibrahim.

“There should have been a win-win solution for both sides, instead of the constant pressure on Ibrahim Libya to give himself up and be locked away under the ISA. He had always said he would never submit to the injustice of incarceration without trial.

“Many had begged him to leave the country, and to return when things calmed down. He said he didn’t have it in him to abandon his pupils and the villagers of Memali. I remember him saying, ‘If anything is to happen to me, let it happen here, in my village,” he said.

This KiniGuide was compiled by Koh Jun Lin.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.